I paid more attention to the world chess championship match in Dubai last month than I have given to chess over the last thirty years. I’m nut sure why – perhaps I was just curious to see if the Norwegian Magnus Carlson would be able to win yet another title and retain the world championship for a full decade.

A neighbor had taught me the rules of chess while I was still a teenager. I was never able to beat him more than perhaps a third of the time, but we had great fun. I found other people to play with from time to time all through graduate school. It was only later that I discovered that I and my playing companions were what serious chess players call “wood-pushers”. This was a derogatory term that described anyone who just made more or less random moves on the chessboard. Even though they followed the rules of chess, they reflected absolutely no understanding of the most elementary elements of the game.

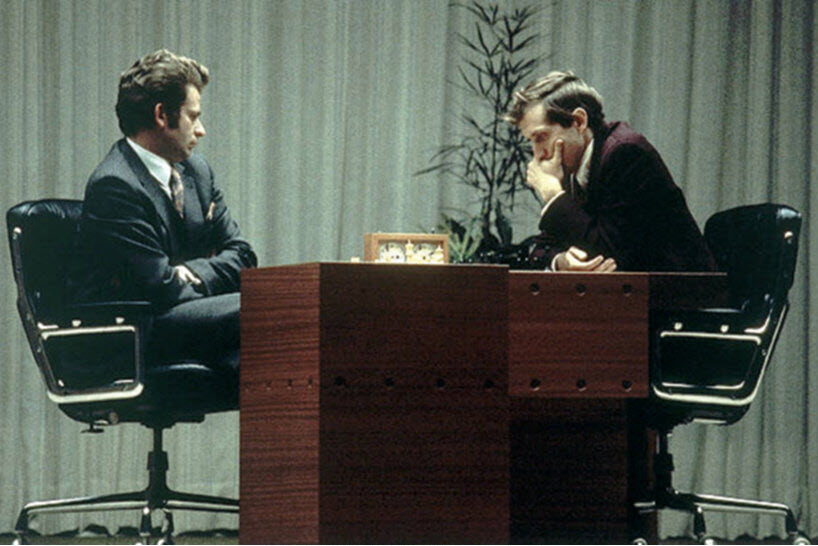

Then stories about an American named Bobby Fisher started appearing in the newspapers. He had won the regional qualifying tournament and was now seeded into the final eight candidates who would play matches to determine who would be the challenger for the world championship in 1972. The defending champion was the Russian, Boris Spassky. One Russian or another had held the title since the end of WWII.

When Fisher won the first candidates match by winning every single game against a top-flight Russian grandmaster, the trickle of newspaper articles on page 10 of the newspapers exploded into a tsunami of front page headlines. Fisher became the face of America in the so-called cold war.

The semifinal match against the Danish grandmaster Bent Larsen was played in Denver, Colorado, where I was living at the time. Fisher won and again by a perfect 6-0 score. It was an unforgettable experience to be immersed in the kind of insane excitement that seemed to be everywhere around me – and I too began to look more closely at the strange tables reproduced in magazines and newspapers that documented every move made by both players.

In the final candidates’ match, Fisher would face a former world champion, the Russian Tigran Petrosian. Could he manage a third 6-0 win? There was no internet in those days, so I was up early every morning to turn on the news and find out the result. As it turned out, Petrosian won one game and managed three further draws while Fisher won five games – meaning that he would be the one to play Spassky for the world championship.

As I studied more and more closely the reports of the games, I became increasingly intrigued by the mysterious comments by the top professional players in the world. Comments that were almost entirely incomprehensible to me, but hinted at a level of strategic and tactical complexity that was totally foreign to me.

So, I did what I always did in those years: I bought two or three books about chess and started reading.

Do you remember when you were a teenager and you fell madly in love for the first time? It was like that for me except that the object of my passion was the 64 squares of the chessboard.

I could think of nothing else and my dreams were filled with chess diagrams and matches. I read, I studied, I set up my board with the chess pieces and started playing through the championship games that were described. I struggled to understand the comments and strange concepts – things like “controlling a long diagonal”, “launching a king-side attack”, and “creating mobility”. My poor wife at the time had no idea what was going on.

Something curious happened by the time the championship match was over: the people I had enjoyed playing chess with before all of this started no longer wanted to play with me. I guess they didn’t enjoy losing so quickly and then listening to my detailed analysis of their mistakes.

I joined a local chess club to find better competition. It was there that I discovered just how big a gap there was between casual and serious players. Undeterred, I continued to study and to go to the bi-weekly meetings. I would sit down at the table with a player I had never met before and we would start playing. Two, three or four hours later we would get up, shake hands and go home. I think I was vaguely aware of the fact that I knew nothing about him, often not even his name.

I rather quickly moved up the ladder in the club rankings and then decided to participate in a local tournament. It lasted an entire three day weekend. There were probably more than 200 of us in the room and there was almost dead silence the entire time, other than the thunk of pieces being set down and the occasional click of 200 tournament clocks as a player made his move, turned off his timer and started that of his opponent.

I had a mediocre result in that first tournament, but it fired up in my ambition to do better. Just study more! Practice more! Apply the techniques described in the books!

My chess library had probably expanded to 30 or so books by this time. I thought this was heaven! I entertained fantasies of being the next American after Fisher to be in the world championship finals. I did much better in the following tournaments and my ranking rose rapidly.

Within two years I was somewhat better than the average serious chess player and also, quite curiously, now divorced. That was sad, but I was consoled by my new love of those 64 squares. I was sure it was only a matter of time, study and practice until I would achieve a chess master rating and beyond.

Strangely, it didn’t work out that way. Despite endless hours of studying and practicing, I was no longer able to achieve a better result in tournaments. I started losing games that I should have won because of mistakes and oversights. All of my hard work and insights from my study of chess now became a source of discouragement. I would replay some of the games that I lost in the last tournament and could clearly see my strategical failures. Why couldn’t I see them while I was playing?

No matter what I tried, I was just stuck. It was like a passionate teenage love affair again – so wonderful in the beginning but now she was leaving me. Paul Simon’s song about young love kept running through my head: “August, die she must/The autumn winds blow chilly and cold/September, I’ll remember/A love once new has now grown old.”

So, I put the game away and didn’t play another game for many years. Oh, I would occasionally open the drawer where I had put my tournament chess set and clock and feel a twinge of nostalgia before closing it again. When computerized chess applications became available, I played a few games with my iPhone as my opponent. If I set the level on the “dumb scale” low enough, I could usually win. Turn it up one level and I would almost always lose. After missing my S-Bahn stop a few times, I put that away as well.

So thank you Magnus Carlson for the invitation to look at the faded picture of my old love of the 64 squares. I suppose I should also thank your opponent, Ian Nepomniachtchi, for showing me that even the very best players in the world can make really dumb mistakes. I find that, somehow, a bit consoling.

Great article

Thanks, Curt. I still remember that tournament game that we played so many years ago.