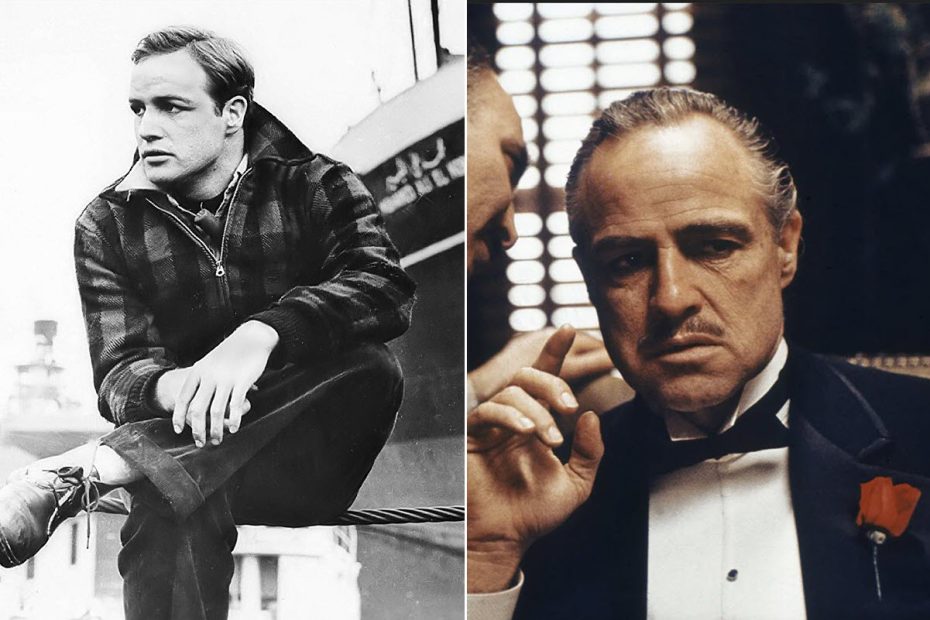

I expect that we all have seen plays and movies where you have no sense of the actor at all – only the character in the story. When you see the same actor in different stories, their very different character is again the only thing you experience. Marlon Brando in On The Waterfront (above left) and in The Godfather (above right) is a perfect example. Then there are others, imminently forgettable, where the actor seemed inauthentic and unengaging. What makes the difference?

Credibility of the portrayed emotion is something else entirely. My first personal experience of this was in my early thirties. It was a difficult time for me and it seemed like every possible thing that could go wrong was happening at the same time. When the pastor of my Unitarian Church decided to do a little play one Sunday based on the trials of Job, I agreed to read the part of Job. None of us knew anything about acting and we were mostly just reading the script rather than performing it. The audience was rather restless, talking to one another, and mostly ignoring the kids who were running around and not paying much attention. I got to the point where Job asks God, “What did I do to deserve this?” and all my frustration and confusion about what was happening in my life seemed to explode in my head as I spoke that line.

I see in my mind’s eye even today the audience at that moment: there was sudden, total silence and even the kids stopped and stared at me. I swear we were all breathing in unison. The woman who was supposed to read the next line looked at me in shocked surprise for a moment, then remembered that she was supposed to read the next line. We continued on and everything in the church sanctuary resumed as it was before.

I suppose, in one way, the rest of my creative life up until this day has been devoted to trying to understand what happened in that one moment.

A few years later I discovered a weekly TV program called The Actors Studio. The host, James Lipton, would interview famous actors and explore how they had prepared for their roles in their Oscar and Emmy winning performances. I watched it regularly and still have many DVD’s that I recorded.

All of the actor guests were permanent members of The Actors Studio, founded in 1951 by Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan. Each actor had a unique story about how they learned their craft, yet there seemed to be a common thread. All had been trained as actors in something called “The Method”. This was based on the work of Konstantin Stanislavski:

- Use both your sense and affective memory;

- Talk like people in conversation;

- Ask yourself, “What if the conditions on stage were real?” and then proceed accordingly (Stanislavski’s so-called “Magic If”);

- To get audiences to suspend their disbelief, you as the actor must suspend yours.

Strasberg encouraged his actors to comb through their own lives for strong feelings that could fuel their work onstage. When had they felt pain, joy, anger? When their mother died? When their father left? Use it. “Don’t deny your emotions, be proud of them” he said.

This all seemed to explain in part my experience from years before in the church play. Still, it had been a total accident and I had no idea how it might actually be useful to me if I ever went on stage again.

Nevertheless, the seed had been planted and I began watching movies and stage plays with new eyes, noticing when a performance really touched me (I wrote about Fiddler On The Roof last year). The common thread seemed to be that with an authentic performance I felt the emotions within myself that were being portrayed on the screen.

Flash forward a few decades. I had recently retired from a career in IT and project management when my wife saw a flyer for a play being put on by Entity Theatre and asked if I wanted to go. There was no hesitation – that seed planted so long ago suddenly burst into life. The poor woman who sold us the tickets at the top of the stairway to the theater had to listen to my whole story about the Job play before we accepted our tickets and found our way into the theater.

I enjoyed the play but my real objective was to find out how I could get involved in future stage work. Almost every role had been cast for the following Spring and Summer but the director of the Shakespeare play As You Like It said I could play the role of one of the sheep if I wanted to. Yes, anything! My only line was “Baaa”. There were two other ladies playing the part of other sheep as well so I became the black sheep.

We had the best time during rehearsals and the performances just making stuff up: when we would say Baaa to make fun of one the the character’s serious speeches or promises, interacting with the other sheep characters in a way that mimicked the silly story and so on. I wasn’t trying to perform, didn’t have any expectations – I was just having a fun time (and yes, I really enjoyed it when our antics got a laugh from the audience).

When the Summer performances were over, I noticed something I found a bit strange: whenever the subject of As You Like It came up in conversation, the response was almost always something like, “Oh, the one with the funny sheep.” My fellow performers reported the same thing in their interactions with others (not necessarily with a positive attitude!). What had happened? I was determined to find out.

It has only been recently that I have realized that that determination to “find out” marked the moment when I stopped just being myself. In the next play I was in, I tried to “be” my character on stage. It was OK, I guess, but it was also the point where my performance seemed to stop touching people in the audience.

Following my life’s pattern, I started buying books and trying to “figure things out.” Some of the reading was useful, of course. I learned about the “schism” in the Method acting school. I read Stella Adler’s posthumous book, The Art of Acting, and Sanford Meisner’s books where he focused on the actor’s relationship with others on the stage and their ability to improvise responses in the moment. One of his quotes stood out for me: “Acting is living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.” I wrote a bit about this in a prior blog.

I continued to participate in other plays and workshops. I was shocked at how one director would assert that “Method is crap” and a workshop leader would be similarly disparaging of Meisner or Adler. Still, knowing my inclination to strike off on my own even when I had no idea of what I was doing, I really tried hard to follow the guidance I was getting from the leader of whatever project I was involved in.

It wasn’t really working. My performances were mostly dull and lifeless, my attempts to express emotion either unconvincing or overly dramatic.

Then I came across another quote from Meisner: “To be an interesting actor, you must be authentic. For you to ever be authentic, you must embrace who you really are. Do you have any idea how liberating it is to not care what people think about you? Well, that’s what we’re here to do.”

That really resonated with me as I realized I can’t authentically be anyone other than myself, neither on the stage nor in real life. If I have emotional memories of traumas that are relevant to my character in a play, I can use those. If not, I can work with imaginary circumstances. What difference does it make if my strongest emotions come from something that happened to me or from something that I imagined?

So, that night I went into rehearsal committed to just embracing who I was and not worrying about whether I was good enough or whether I was “doing it right.” Afterwards, I was riding home on the same train as the director. He suddenly turned to me and asked in a puzzled tone, “What happened tonight? Your performance took a quantum leap.”

It was still only a beginning. I still have so many emotions and fears that I’m unaware of or am afraid to disclose to others. If those are some of the very emotions and fears that my character is struggling with, I cannot portray that character authentically without acknowledging and accepting them within myself. If I am willing to do that, then I open myself up a bit to a more robust connection with my life. How wonderful!

Practicing emotional connection on the stage is also learning to connect more fully with everyone around me in my real life. I’ll never be finished with this exploration as long as I’m alive, but it is an extraordinary and exciting journey for sure.

If you’re interested in exploring this topic personally, check out our upcoming acting workshop here.

Thank you for sharing your journey in life, Roger. Your insights are great contributions to my own explorations.

…as yours have been to mine. It’s very special that we have contributed to each other’s lives in this way.

Well said and very interesting.