When I was asked last year if I might be interested in playing one of the parts in Harold Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter, I had to admit that both the play and the playwright were unfamiliar to me. I borrowed a copy of the play and read through it that evening.

Two men are waiting in a basement room. Gus, the junior partner, constantly wanders around the room. He asks lots of questions which Ben, the senior partner, tries to ignore, deflect and ridicule. It gradually emerges that they are hired killers waiting for their next job, but something is disturbingly different about this night.

Ben finds security in just following orders without question. Gus seeks explanations for everything that he doesn’t understand. In the end, Ben is forced to confront the consequences of his blind obedience and Gus realizes the cost of allowing Ben, his boss, to override all of his concerns.

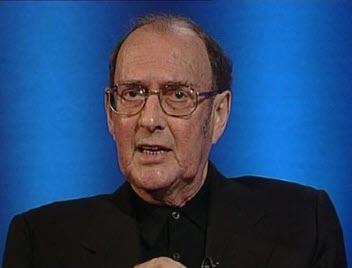

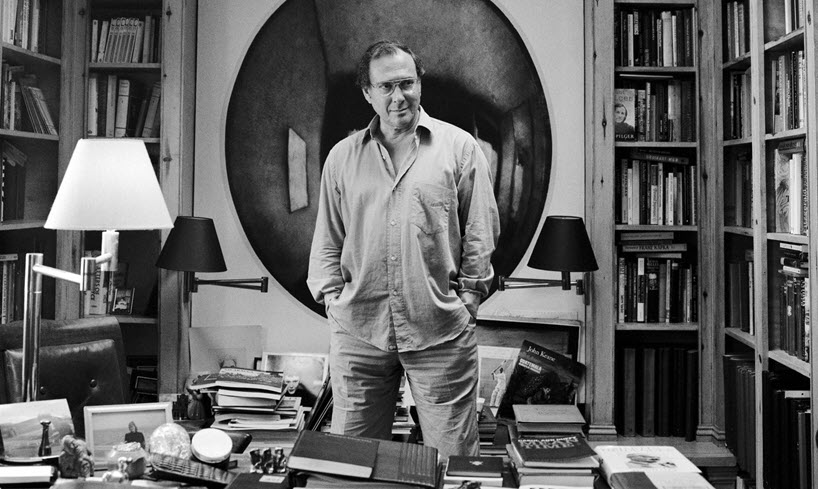

It was a disturbing play, to say the least, and I wanted to find out more about the author, Harold Pinter. As I read about him on the internet, I felt increasingly embarrassed that I had gotten this far in my life without knowing that Pinter was considered to be one of the most influential modern British dramatists with a career spanning more than 50 years as a playwright, screenwriter, director and actor. What was more, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005. He was unable to travel to Stockholm at that time as he was seriously ill with cancer, so the Nobel Committee allowed him to video-record his acceptance speech.

If I thought the play was a bit disturbing, his speech was profoundly so. He began with a brief description of his “search for truth” as an artistic process and then devoted the rest of his speech to demonstrating how the “avoidance of truth” was the cornerstone of power politics:

“Political language, as used by politicians, does not venture into any of this territory [of the artist] since the majority of politicians, on the evidence available to us, are interested not in truth but in power and in the maintenance of that power. To maintain that power it is essential that people remain in ignorance, that they live in ignorance of the truth, even the truth of their own lives. What surrounds us therefore is a vast tapestry of lies, upon which we feed.”

He went on to excoriate the United States and Great Britain for their roles in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq and the Middle East over the decades following the Second World War, asking what we, as individuals had done to try and prevent all the atrocities. He ended his speech with this:

“I believe that despite the enormous odds which exist, unflinching, unswerving, fierce intellectual determination, as citizens, to define the real truth of our lives and our societies is a crucial obligation which devolves upon us all. It is in fact mandatory.

“If such a determination is not embodied in our political vision we have no hope of restoring what is so nearly lost to us – the dignity of man.”

This was no idealistic assertion made from some safe space free from the consequences of protest. He was heavily criticized for his blunt political statements and ridicule of the British and US governments. He was personally demeaned as an ethically flawed man with a deeply fractured moral compass. His speech, though, simply continued a life-long commitment to perspectives and actions in which he believed.

He refused to comply with the requirements of the British National Service as a conscientious objector to military service (1948). He was an early member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and had supported the British Anti-Apartheid Movement beginning in 1959. The Dumb Waiter, written in 1957, may well have been intended as a political drama showing how the individual can be destroyed by a higher power. Ruby Cohn expressed it this way:

“Each of Harold Pinter’s [first] four plays ends in the virtual annihilation of an individual…. It is by his bitter dramas of dehumanization that he implies ‘the importance of humanity’. The religion and society, which have traditionally structured human morality, are, in Pinter’s plays, the immoral agents that destroy the individual.”

Pinter continued his political activism throughout his life. He signed the mission statement of Jews for Justice for Palestinians (2005) and helped launch the organization Independent Jewish Voices in the United Kingdom (2007). He was still writing in support of the Stop the War Coalition in 2008. He agreed to become the president of the Central School of Speech and Drama just a few months before his death on Christmas Eve, 2008.

By this point I was clear about how much I wanted to have a role in the proposed performance of The Dumb Waiter – if for no other reason than to look at my own attitude about participating in public protest against the actions of government and large corporations.

I have shared in previous blog articles about my childhood and adolescence where being loved was conditional on “being a good boy” and always doing what I was told. Getting involved in the protests against racial injustice or the involvement of the US in the Vietnam War just never occurred to me.

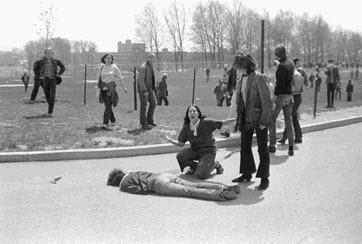

The truth of Pinter’s assertion, that I was living in ignorance of the truth, even the truth of my own life, began to be dimly apparent in the weeks following the shootings at Kent State University. Four unarmed students were shot dead and many others were seriously wounded by National Guardsmen. Surveys in the following weeks showed that nearly two-thirds of Americans believed that it was the fault of the protesters. There was something terribly wrong, yet the consequences of protesting could clearly be enormous. It was the beginning of a long and painful series of discoveries about the “truth” of our involvement in Vietnam, “truth” as Pinter described it – a means to maintain political power.

After the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the toppling of Taliban rule there, the US government decided to “complete the job that been started in the Gulf War.” The justification followed the same pattern of political “truth” that Pinter described. The actual truth was that Saddam Hussein did not have weapons of mass destruction, he did not have “weaponized anthrax” and he was not harboring and supporting the terrorist group al-Qaeda as asserted by the US.

There were large protests against the invasion around the world and especially in Europe. I was living in Germany by this time but had no idea how I might get involved in any kind of action that might make a difference. I just followed the whole, sad story for years.

Fast forward to 2020. The Covid pandemic had shut down so much of our normal life and just going out into public spaces was very risky. Then at the end of May we learned about George Floyd, an African-American man who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The “truth” that the police and city government would have us believe was that Floyd tried to use a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill and then resisted arrest. It was not counterfeit and a video recording showed clearly that he had not resisted arrest.

Protests erupted throughout the US and then to Europe. When one was announced for Königsplatz in Munich, I somehow just knew I had to participate – it was time to let go of being a “good boy” and get actively involved, regardless of the risks.

Being part of a protest crowd is so very different from seeing one in a picture or on television. I found a spot near the Propyläen gate where I had a good view of the speaker’s podium. As I looked around me, I realized that I was in the same space where Hitler had conducted his Nazi rallies in the 1930’s and 40’s. The sense of connection and symbolism was as intense an emotional reaction as I have ever experienced.

After a couple of hours of speeches, everyone dispersed and headed home. There was no incident, no problem, no misbehavior that I saw. “Just a walk in the park,” one might say.

Did my “protest” make any difference? Probably not. Did I “bring unflinching, unswerving, fierce intellectual determination, as a citizen, to define the real truth of my life” as Pinter demands? I’m less sure of the answer to that. Perhaps it was a beginning.

Perhaps my playing the role of Ben in The Dumb Waiter will be a continuation.

Pingback: The Dumb Waiter – Voight Post Script

Thank you for this Roger!

Thank you for posting Roger. More food for thought.

I wonder if we Earthlings’ will ever be able to ‘change the needle’ or are we doomed to dwell in a trap of repetition?

So many writers have pointed the way. “Was bleibt schaffen die Dichter.”