One of the thousands of adoptees from the Tennessee Children’s Home Society (TCHS) read Lisa Wingate’s novel Before We Were Yours shortly after it was published. It resonated deeply with her and she wrote to Lisa with the suggestion that some of the adoptees might meet somewhere to share their stories. Excited but also intimidated by the amount of work that would be involved and the need to document the stories, Lisa enlisted her long-term friend and journalist Judy Christie to help with the project.

The result was the companion book Before and After, published in 2019. It reads a bit like a journal that Judy wrote as she traveled in the six weeks leading up to the June, 2018 reunion in Memphis, interspersed with the personal stories of twelve adoptees. They were all given pseudonyms in the book to protect their privacy. I’ve had the honor of getting to know a couple of them via e-mail and video calls. The experience of sharing our memories and stories has been nurturing and healing.

Here I want to share my story in the hope that it may bring solace and connection for other adoptees in this widening circle. It has so many common elements with those described in the book, yet each one is unique and describes a path to a successful life despite the trauma of its beginnings.

Wingate begins her novel in a delivery room where the mother has just given birth to a stillborn baby. The father is in the military and far away, so it is the grandfather who gets the news first – along with the warning that the mother should not attempt to get pregnant again as it could be fatal for both the mother and her future child. Seeing the grandfather’s profound disappointment and despair, the doctor adds that adopting a child might be a possibility and that he should get in touch with Georgia Tann in Memphis.

My mouth dropped open as I read these first pages. It was during the depths of the great economic depression when my future adoptive mother (Vesta) had a life-threatening medical emergency because of an ectopic pregnancy[1]. The doctor said that it was highly unlikely that she could get pregnant again and that it was probably not safe to even try.

My future adoptive father (Luke) was as devastated by the news as was Vesta. As the economy began to improve, they explored the possibility of adoption but, as the Second World War had already begun in Europe, it was not realistically possible to seriously look for a child. By the end of the war, Vesta was already in her forties and they were considered too old to become adoptive parents.

Then in 1947, a friend introduced them to Smiley Burnette who told them about the possibility of adopting a child from Georgia Tann at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society (TCHS). They quickly began the application and adoption process.

In Wingate’s novel, the children from her fictional family struggled with an alcoholic father, lived on a shanty boat near Memphis and had little opportunity for education. In my biological family, it was my mother, Winnie, who was alcoholic and absent for long periods of time.

Her husband, Glenn, grew tired of the failing relationship and had left her sometime in early 1944. Winnie probably went to Chicago to visit her sister, Bernice. Sometime during that visit she got involved with a man and became pregnant. Nine months later, for reasons that will never be known, Glenn paid for Winnie’s hospitalization and agreed to have his name shown on my birth certificate as being my father. When Winnie conceived a second child, Patricia, out of wedlock some two years later, he again consented to be shown as the father on her birth certificate.

Winnie continued to drink heavily and to be absent from home for days at a time, leaving me (and later, Patricia) in the care of her mother, Maud Wilhelm. Increasingly distressed by Winnie’s irresponsible activities – and probably feeling a bit overwhelmed with now having two young children to be cared for – Maud asked Bernice to come to Memphis to help out. Bernice was very pessimistic that Winnie would change her ways. Maud and Bernice decided that it would be in best interests of Patricia and me to ask the Memphis Juvenile Court to intervene.

They surely had no idea that their good intentions for our welfare would simply feed the illegal adoption juggernaut that had been going on with the TCHS for more than 20 years. It took less than three weeks to complete the forms and go before Judge Kelley who, behind closed doors, ruled that we were not properly cared for, should become wards of the state, and be turned over to the TCHS for adoption. As Winnie was being hurried out of the hearing room she saw us for the last time – I was apparently sitting on the floor on the other side of a glass door, holding 1-year-old Patricia in my lap.

I have a number of memories from my time in the orphanage. I remember being in a corner room with four or five cribs. I remember one night in particular when I awoke while it was still dark and I was very frightened. I was sure that the orphanage people had abandoned me, just as I imagined my family had, because I had not been a good enough little boy. I stood at the end of the crib nearest the door and screamed loudly for someone to come – but there was no one. I became very angry and finally threw myself down on the bed, sobbing, and promising myself that I would never, ever need help again from anyone else. It was, perhaps, a necessary survival strategy at three years old, but that decision has colored and shaped my entire life – long after I had any need of it for survival.

I have another clear memory of some people coming into this crib room one night and shining a flashlight on my face. I did my best to pretend to be asleep and remember a woman’s voice saying, “Oh, he’s just adorable!”

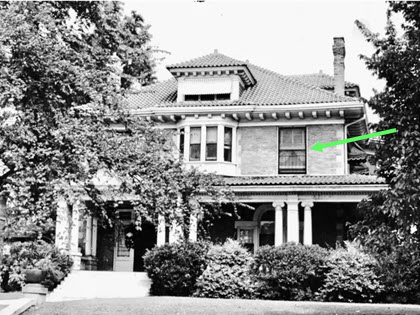

I can remember wandering over to one of the corner windows and looking through fresh green leaves at the cars going by on the street below.

Then there came the morning when one of the staff dressed me more carefully than usual and in nicer clothes. A women in a nurse’s uniform then led me, along with a few other young children, down the wide wooden staircase to the first floor and then out the front door. We got into a large, black car which then took us to what must have been the Memphis train station.

It seemed to me like we were going to stay on that train forever. When we were finally allowed to get off, the nurse led us into an enormous building[2] that seemed big enough that a mountain could fit into it. In my next memory there are no other children, just a strange man and woman – Luke and Vesta, my adoptive parents, talking to the nurse for a bit. Suddenly, without a single word to me, she turned and walked away, leaving me with these strangers. I cried, reaching after the nurse, fearful that I had been a very bad boy again and she was abandoning me.

My new adoptive parents did their best to console me and get me to stop crying – but I was utterly terrified and nothing could make any difference – at least not until my new dad offered me an ice-cream cone if I would be a good boy and stop crying! It was the last part that made the difference – the nurse was gone and what I heard was, “stop crying or we will abandon you here in the train station.”

And so my new life began. I have copies of some letters where Vesta wrote that I was constantly asking for my sister. Vesta was required to write to Georgia Tann every other month during the adoption probationary period, and she asked in those letters whether it would be possible to also adopt my sister. Georgia Tann’s replies were filled with falsehoods, claiming that there was no sister and another female adoptee was not possible “at the present time”.

The facts were that that my sister Patricia had been adopted by a family that happened to live only a few blocks away from Luke and Vesta’s house and that her adopted name had been changed to Lauren.

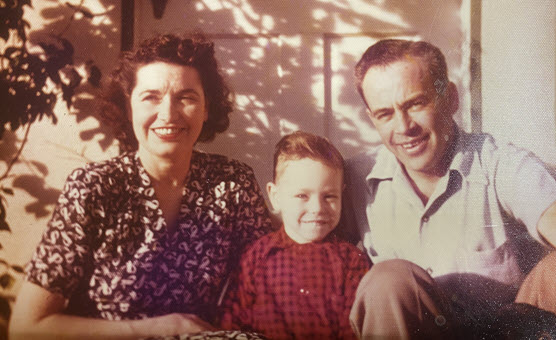

My adoptive father, Luke, was really happy to have a son and spent a great deal of time with me – playing sports, helping me to build things, taking me on fishing trips and, as I got older, helping me with school subjects. I was only five or six years old when he made a multiplication table on a big sheet of drawing paper and had me memorize it. I was so fascinated by it that I extended it myself from 9×9 to 20×20 and learned all of those as well.

He would have me read assembly instructions for kits that he bought and then assemble them myself (with his supervision). He was very disciplined, though, and if I missed a step, he would make me take the whole thing apart and reassemble it correctly. To this day, when I am putting something together, I still feel his presence and follow the approach he taught me.

My adoptive mother, Vesta, had me reading by the time I was five years old. We played card and board games almost every afternoon. Scrabble was one of our favorite games. Mom changed the rules a bit, though. We would play fourteen letters at a time rather than seven, and she would encourage me to scour the dictionary to find words that I could play using the available letters already on the board. She clearly saw it as a fun way to encourage me to learn new words rather than just a competition for the best score.

Both of my parent’s behavior toward me began to shift when I was around eight years old. My father began to drink more and to become much more controlling of what I was allowed to do or places that I could go. My mother had less time for afternoon games and began to say things that simply were not true about what I had done or what I had said. Both of them began telling me that I wasn’t adopted at all and would become very angry when I would recount some of my memories. Although it was never discussed, I suspect that the revelation of the TCHS scandal was absolutely devastating for both of them.

My teenage years were very difficult. My mother followed a slow spiral into mental illness where she could not distinguish reality from fantasy (ultimately diagnosed as schizophrenia several decades later). My father’s alcohol problem reached the point where he would frequently be drunk at night. If I said or did something to displease him, I could expect to be beaten up.

He often said that college was a waste of time and, if chose to go that direction, he wouldn’t pay a penny of the costs. Fortunately, I was the valedictorian for my high school class and was offered a scholarship at UCLA. I was also able to get a part time job with one of the professors there and secretly earn enough money to pay my own way. (My promise in the orphanage that “I will never depend on anyone else for anything ….” again). I left home for good as soon as I could manage it and had very little contact with my adoptive parents for the next 17 years.

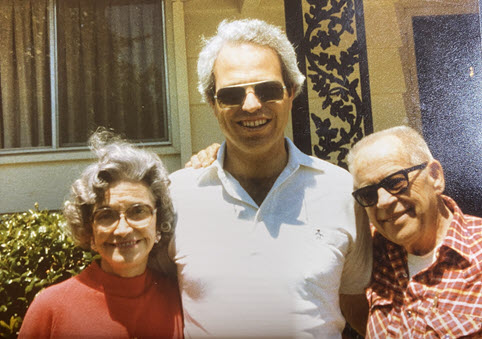

That orphanage promise to never need anyone else played a big part in two failed marriages and getting fired from several jobs because of my anger outbursts and difficulty in working with other people. I enrolled in some workshops that promised to show me how to be successful and happy. It was an emotionally brutal experience but it made clear to me that I was the source of most of my problems. I committed to the Buddhist faith and spent some time in therapy and workshops. I reconciled with my adoptive parents and met and married Susan – who somehow almost always manages to accept who I am while showing me what I could be.

Three months after we were married, I got an unexpected phone call. My biological sister, Lauren, had been able to obtain our adoption processing papers from Tennessee and thus able to locate me. It was the most amazing 45-minute phone call I have every had. We agreed to meet early the following year (together with our spouses) in Santa Barbara, California.

It turned out that Lauren had also been through two failed marriages before finding her perfect mate and that I had a niece (with three children) and a nephew, all living in the Palmdale desert area north of Los Angeles.

When all of the records in Tennessee were finally made available to adoptees, Lauren was able to locate our biological mother, Winnie, who was living in Florida. I flew out to see her in person in 1998. It was an emotional meeting, to say the least. Winnie had remarried and had born him four daughters (who now had children of their own). Over the following years I found out that Winnie’s second husband had been involved with several other women, resulting in several additional children. Although technically these other children were not genetically related to me, our common story created a huge, extended family. This was a bit of a shock for me, having thought for most of my life that I was an only child.

The process of being immersed in the very difficult lives of all the offspring of Winnie from her second marriage and unravelling all the connections in this extended family is an ongoing process. It has been like having a glimpse into an alternative universe where I had remained with Winnie and had been forced to grow up in that environment. For all the challenges I had with my adoptive family, I believe that my life has been dramatically better and far more successful than it probably would have been because of the love and care that I received from them. This in no way justifies all the terrible things that were done by TCHS, Georgia Tann and Camille Kelley – yet at the same time, I still feel gratitude for the results their actions produced for me.

The two perspectives seem rationally contradictory, yet in my heart they are both true. It is a dilemma that I will continue to explore and try to understand.

[1] An ectopic pregnancy occurs when the fertilized egg implants in one of the fallopian tubes (the tiny conduits from the ovaries to the uterus where fertilization takes place). This invariably leads to severe and life-threatening abdominal bleeding requiring emergency surgery.

[2] The Los Angeles Grand Central Train Station

Pingback: January Program Meeting copy - AAUPW

Pingback: The Sins of the Fathers – Voight Post Script

I remember you telling me bits and pieces of this story. I am still overwhelmed by it, and I need to process it further. From time to time, your story resonates with my own: fear of abandonment, becoming an island, and probably more. Still, it’s a harrowing experience, and I am happy it continues to lead to a positive outcome in your life despite all of these hardships.

I have been reading a lot about Georgia Tann. Did she just take children from her local area? My family member was in an orphanage and was sold, but not in Tennessee.

As far as we know, the children did all come from the Memphis area and surrounding counties. Since Memphis is right on the Mississippi River, that would have included some areas in eastern Arkansas as well. The scandal around TCHS and Georgia Tann attracted a lot of media attention, but the the impact of adoption on the adoptees and their children is pretty universal. I would encourage you to show the books and the blog posts to your family member and see what resonates for them.

Pingback: January Program Meeting - AAUPW