It was with great sadness that I read of the death of the Israeli actor Chaim Topol a few weeks ago. He began his career as a stage actor where his performances were so authentic that he was soon invited to star in movies (more than 30 over the course of his lifetime). One of those was the story of the impoverished milk farmer Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. He was nominated for the Oscar Academy Award for Best Actor and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor for his performance. The brief movie clip they played during the Academy Awards looked intriguing.

I was in the army at the time and assigned to Fitzsimmons Medical Hospital. I was a Medical Service Corp captain with a newly minted doctorate degree when I arrived in the fall of 1970. I was filled with that youthful certainty that I now had all the tools I needed to be a smashing success in whatever endeavour I might undertake. I was sure that my intellect and ability to quickly assess a problem and reduce it to the essential elements was all that I needed to be successful. Things like art, drama, dancing and creative writing were nice for relaxation and escape but weren’t at all important for my daily life.

One spring day in 1972 I noticed that Fiddler on the Roof was playing at the small theater on the Fitzsimmons army base. It had been a particularly strenuous day and it seemed like a movie night out would be the perfect way to relax.

It was a beautiful spring evening and my wife was easily persuaded. Although it was over fifty years ago, the picture in my mind of that evening remains vivid to this day. We were already well into daylight savings time. The sunset colors seemed to make the fresh spring green of the new leaves especially vivid. Even the broad shadows from the trees had a warm undertone. The sandstone walls of the theater seemed almost golden.

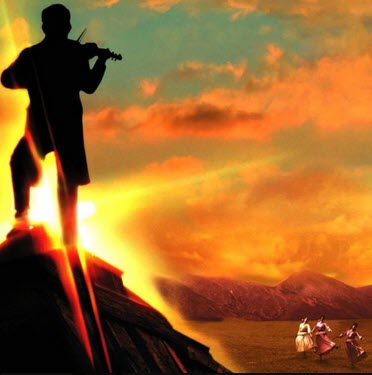

We settled into our seats with a shared tub of buttered popcorn. I was physically there, but my mind was far away, thinking about something work related. Then the lights went down and a bearded, Jewish milk farmer appeared. He is in a small Russian shtetl in the first years of the 20th century. He was pulling a wooden cart, delivering fresh milk that he had taken from his cows’ udders just that morning. As he makes his deliveries to one house after another in his small village of Anatevka, he speaks of his wife, his children and the other villagers. He admits that there are many challenges of coping with life. “How do we know what to do?”, he asks rhetorically, and then answers his question with an explosive rendition of the theme song, “Tradition”. The opening sequence ends with a fiddler playing a violin while standing on the roof of a small house. I was mesmerized, and it was only the beginning.

I learned that the milk farmer’s name was Tevye, that he has been married for more than 25 years to Golda and that they have five daughters. The oldest, Tzeitel, is madly in love with the tailor Motel and is horrified by the matchmaker’s choice for her future husband – a butcher who is the same age as Tevye.

As the sun is setting on a Friday evening, there is lots of conversation as everyone hurries to gather around the table for the beginning of the Sabbath. The mad scramble suddenly transforms into a great calm as Golda begins the ceremony of lighting the candles. She sings the Sabbath prayers to a hauntingly beautiful melody composed by John Williams. My sense of the importance of tradition that Tevye sang about in the movie prologue deepened and intensified.

When Motel gathers the courage to tell Tevye that he wants permission to marry Tzeitel and Tzeitel says she loves him very much, Tevye agonizes over the forced choice between the tradition of honouring the choice of the matchmaker and his love for his daughter who wants to choose her own husband.

He ultimately gives his permission but clearly wonders what love really is, after all. In another beautiful musical piece, he asks Golda (whom he met for the first time on their wedding day) if she really loves him. In the end, Golda sings of all the ways she cared for and took care of him over the years and asks, “If that’s not love, then what is?”

The marriage ceremony takes place with another beautiful musical number, “Sunrise, Sunset”. As I watched the elaborate ceremony, I got a profound sense of tradition as the foundation of life and connection in the Jewish schtetl. The intrusion of Cossack dancers and Orthodox Christian soldiers that disrupts the wedding celebration is profoundly disturbing and foreshadows what is coming.

Perchik is a young man who has fallen in love with Hodel, Tevye’s second oldest daughter. He is a radical Marxist from Kiev and has joined the revolutionary forces resisting the Tsarist pogrom against Jewish communities. He is at the point of being arrested and sent to prison. Perchik and Hodel have decided to get married and ask Tevye for his blessing, not his permission. Tevye is thus faced with yet another challenge to his faith in traditions – how can he agree to the marriage that his daughter has decided upon when they have not even asked for his permission?

His pain and agony are palpable, yet his love for his daughter ultimately becomes the decisive factor, even as he knows that it may well mean he will never see her again. When Hodel is about to board the train to live near her new husband in the Siberian prison, she says to Tevye, “Only God knows when we shall see each other again.” Tevye replies, “Then we shall leave it in his hands.” I don’t think there was a dry eye in the movie theater.

When his third daughter, Chavaleh, secretly marries an Orthodox Christian and then begs Tevye for forgiveness, he tries to find a way to accept it but finally disowns her, saying, “No! If I bend that far I will break.” It’s so painful, yet my horror at the choice is somehow matched by my recognition of the impossibility of him abandoning his religious traditions.

Soon thereafter, the Tsarist authorities destroy much of Anatevka and order all the residents to leave within three days. They gather one last time in a prayer circle to say good-bye to the only place they have ever know as home. In the beautiful closing song it becomes clear that the traditions leave with them as they depart for other places in America and Europe – and that Anatevka is just a place with “a little bit of this and a little bit of that.”

When the lights came up I realized I had been so engrossed in the film that I had scarcely eaten any of the popcorn in our basket. As the audience headed out of the theater, there was surprisingly little conversation.

Photo: United Artists/Allstar

I was dumbfounded by my emotional turmoil and astonished by the power of this dramatic performance. Tevye expressed the theme so well in the movie prologue when he asked “How do we know who we are and what is expected of us?” He admits that he doesn’t know and that he must rely on traditions.

Tradition says that a matchmaker should choose the husband for an eligible young girl – after all, how can a teenage girl turning into a woman be entrusted with such an important decision? Yet what about Tzeitel’s love for Motel and Motel’s commitment to be a successful tailor and take loving, life-long care of Tzeitel? Tevye’s choice meant that he would have to confront much criticism from his community.

When Hodel and Perchik ask for Tevye’s blessing for their marriage without a matchmaker being involved at all, Tevye justifies his choice by asking, “Did Adam and Eve have a matchmaker? Yes! And perhaps these two have the same matchmaker. May God bless and keep them.”

When Tevye refused to forgive Chavaleh and disowned her after she secretly married an Orthodox Christian, I wondered if he saw the pogrom that destroyed his village as God’s punishment for breaking with tradition. It was very symbolic for me that he motioned to the fiddler on the roof (the metaphor for tradition in the movie) to join them as he pulled his wagon and guided his family away from Anatevka on their way to America.

As we headed to our car that night, it had already turned dark. It was an eerie contrast with a strong sense of an emerging spiritual light in my mind and heart. All I could manage to say – over and over – was that was absolutely the best movie I had ever seen.

I saw more clearly than ever before just how much traditions are a two edged sword. Yes, they help guide us to make important choices in uncertain circumstances, but they can also constrain us from taking the risks to explore new and perhaps better alternatives. In many respects I am still processing many aspects of that experience even today, half a century later.

I thought this would be the end of this blog post, but a few days after Chaim Topol died I discovered there was still another element in my relationship with him and this movie.

I wrote in a previous blog post about my biological mother traveling to see her sister in Chicago where I was conceived from her affair with a man named Howard Dooley. The court records indicated that he was born in 1916, a Baptist of Scotch-Irish descent. My biological mother, however, told me that he was Jewish. I recently decided to use one of the DNA analysis services to settle the question once and for all. When I received the results, they confirmed that my biological father was of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

It was shocking to realize that Fiddler on the Roof was much more than just an amazing movie that had changed my life in so many ways – it was also my origin story. In the movie, as they were leaving Anatevka for the last time, one of the characters announced that he and his family were emigrating to “Chicago, USA.” In real life, it might have been my biological grandfather, Howard Dooley’s father, saying the same thing when they were driven out of their village!

I know nothing about Dooley’s family and none of them are left alive. Any records either don’t exist or were falsified. Still, thanks to this movie, I have some sense of who they were, how they lived, and the hardships they had to face. What a gift. I’m so grateful.

Pingback: Emotions: My Connection To Stage And Life – Voight Post Script

Wonderful account of an interesting insight and personal link. Danke.

You are an amazing blogger. What a special story and how it relates to you. Sallie